Who’s breaching the planetary boundaries?

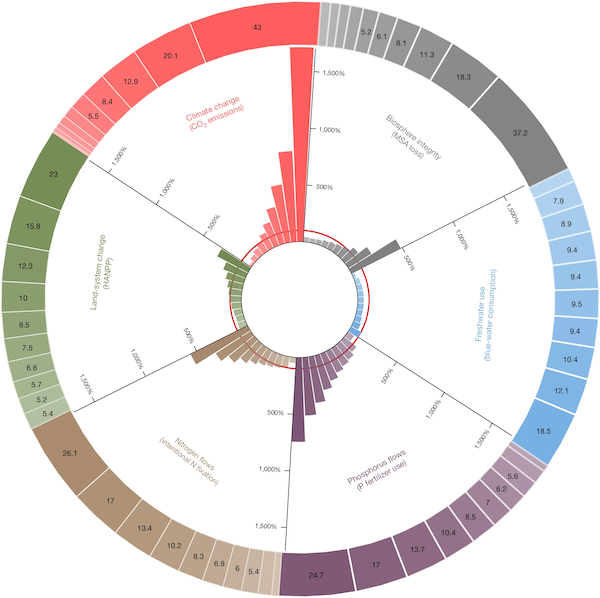

Rampant consumption, unsustainable production, and unchecked resource extraction have driven the planet beyond the stable conditions of the Holocene, breaching critical planetary boundaries. Who bears the responsibility? While the capitalist supply system is undoubtedly a key driver, the wealthiest populations disproportionately contribute to this crisis: in 2017, the richest 10% of global consumers were responsible for 43% of carbon emissions, 23% of land-system changes, 26.1% of nitrogen fixation, 24.7% of phosphorus use, 18.5% of water consumption, and 37.2% of biodiversity loss. In contrast, the poorest 10% contributed less than 5.4% across any of these metrics. Per capita, the richest 10% imposed environmental burdens 4.2 to 77 times greater than those of the poorest. The inequality points to a logical solution: if the top 20% reduced their consumption to the lowest levels within their group, global environmental pressures could decrease by 25–53%. Addressing consumption patterns in food and services alone could reverse critical land-system changes and biodiversity loss, bringing these measures back within safe planetary limits.