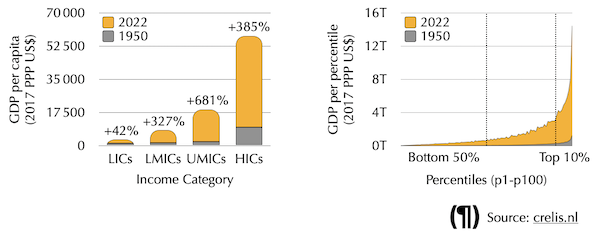

Skyrocketing Income Inequality

Mainstream trade theories might claim that trade growth narrows economic gaps, but the numbers tell a different story. From 1950 to 2022, per capita GDP in low-income countries (LICs) rose by 42%, while high-income countries (HICs) surged by 385%—and that’s just scratching the surface. Accounting for within-country inequality, things look even worse: in 2022, the poorest 50% of people globally took home only 10% of total income, while the richest 10% pocketed around 44%. Even starker, the richest 1% earned nearly as much as the entire bottom half combined. Since 1950, the richest 10% saw income growth 19.6 times greater than the bottom 50%, and the richest 1% saw growth 48.2 times larger. Inequality hasn’t just grown; it’s skyrocketed.

Based on: UNU-WIDER (2023) World Income Inequality Database (WIID) Companion dataset (wiidcountry and/or wiidglobal). Version 28 November 2023. https://doi.org/10.35188/UNU-WIDER/WIIDcomp-281123